Government in Exile: Explorations of the Belarus Enigma

Presentation by Ivonka J. Survilla, President of the Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic in Exile, at the Conference of the Canadian Association of Slavists (Ottawa, 24 May 2009)

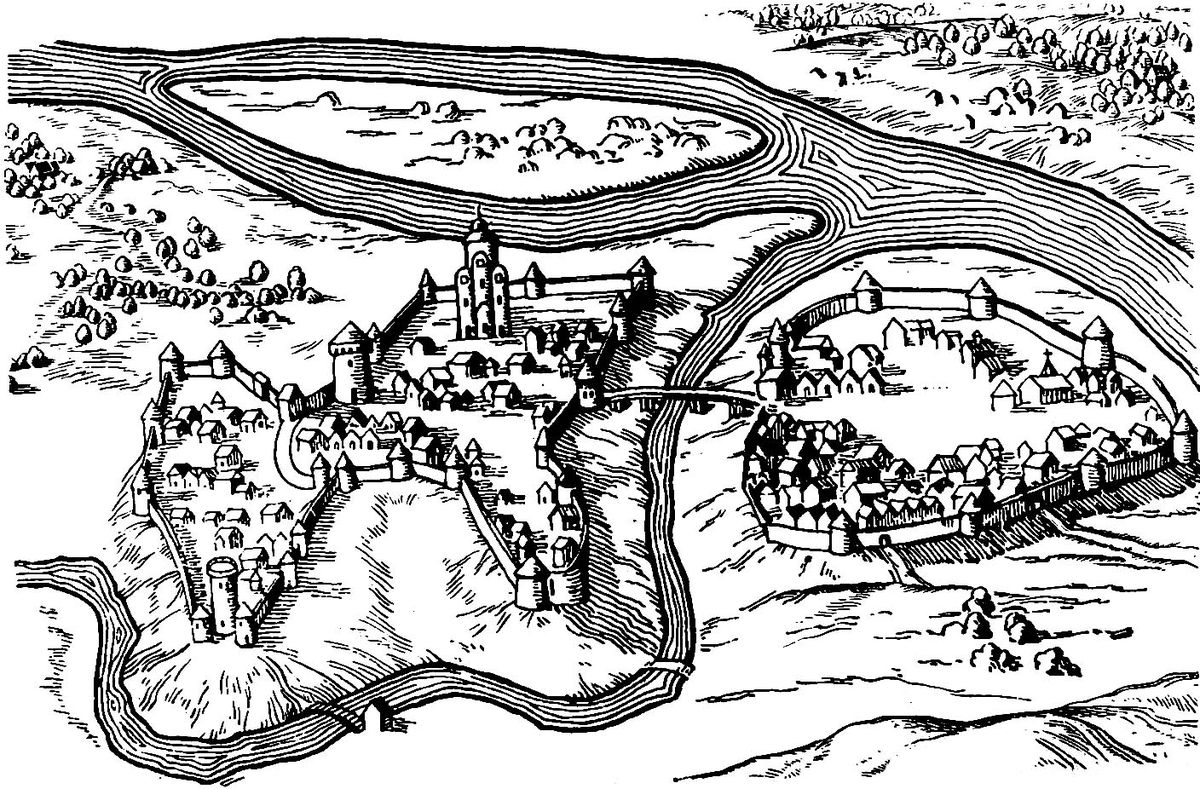

If the sovereigns of my land had been as wise as the emperors of China, they probably would have built a wall along their border with the Duchy of Moscow at the very beginning of her aggressions against their territory. Instead, exhausted by the defensive wars against their Eastern neighbours, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (the medieval predecessor of today’s Belarus), formed a defensive alliance with Poland. This happened in Lublin in 1569. 440 years later, I am speaking to you of the Government of the Belarusian Democratic Republic, which has been in Exile for the past 90 years. Once more – because of the expansionist policies of our Eastern “big brother”.

This presentation explores conditions that have affected Belarus’ existence since the early 20th century. Bolshevik aggression forced a legitimate Government into exile and required its existence beyond the borders of Belarus. In order to understand the present plight of this European nation, there is a need to consider the recent experiential history of Belarus and Belarusians.

At the time that the people of Belarus proclaimed the independence of the Belarusian Democratic Republic (Biełaruskaja Narodnaja Respublika or BNR) on March 25, 1918, 148 years had passed since the first of the partitions of the Commonwealth of the Two Peoples created at Lublin, which western historians have myopically called the Partitions of Poland. 148 years since a big chunk of Belarusian territory had been taken away by our Eastern neighbour. The occupation was completed in 1795, when the rest of Belarus became a province of Russia.

Tsarist rule made the 19th century one of the darkest periods of the history of Belarus. Its people barely survived as a nation. Its culture, its language, its religion, its sense of identity, its dignity had been subjected to a continuous persecution. One response and source for change came in 1918, when the people of Belarus proclaimed their independence.

The Belarusian national flag on the Government of the Belarusian Democratic Republic, Minsk, 1918

The proclamation of the independence of the Belarusian Democratic Republic has been the most important event in the history of modern Belarus. Without it, Moscow would not have accepted to create the BSSR – the Belarusian Socialist Soviet Republic – in 1919 , and without the existence of the BSSR, Mr. Stanisłaŭ Šuškievič (Shushkevich) would not have been one of the signatories of the death certificate of the Soviet Union in the last decade of the 20th century. Thus, it is thanks to the BNR that the independent Republic of Belarus – however imperfect it may be – exists today.

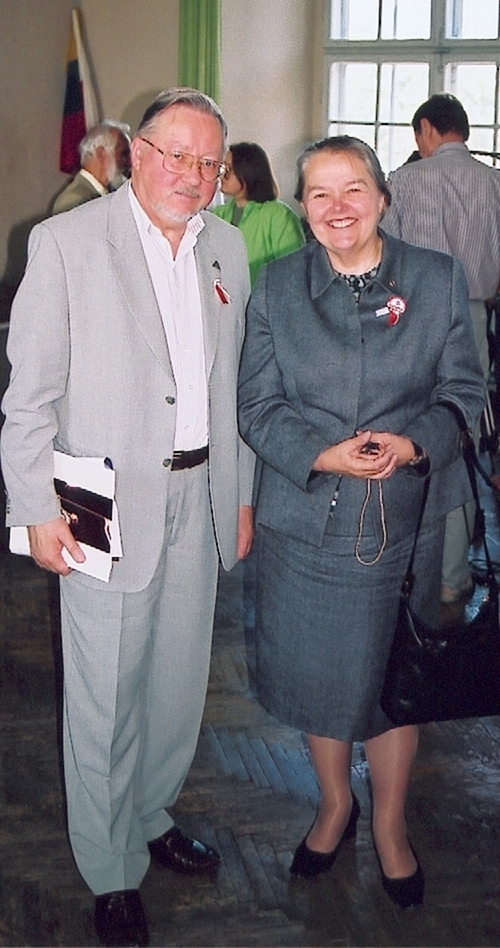

When the Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic was forced into exile by the invading Bolshevik troups, it was welcomed in the Czech Republic, where its two first Presidents in Exile – Piotr Krečeŭski and Vasil Zacharka – resided until the death of Mr. Zacharka in 1943. In his will, Mr Zacharka asked Mikoła Abramčyk to take over the struggle until a new Session of the Rada could be called. At that Session, held in Germany in 1947, Mr. Abramčyk was elected the new President of the Rada, and remained in that positon until his death in 1970. His place of residence was Paris, France. His successor was Vincent Žuk-Hryškevič, a Canadian Belarusian Professor. The fifth President of the Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic in Exile was Dr Joseph (Jazep) Sažyč. I am the sixth President of the Rada in Exile. I have been elected at the Session of the Rada held in New York in August 1997 and reelected for another six years in 2003.

The goal of the Rada of the BNR in Exile has always been and still is to make Belarus an independent democratic Belarusian State, dedicated to implement the values expressed in the three Constituent BNR Charters of 1918. The BNR Rada continues to exist because the conditions of existence of Belarus do not satisfy its concept of a Belarusian State. The international membership of the Rada elects a new Government every six years, which pursues this longstanding mandate.

The first goal of the Rada, Independence, was achieved in 1991. The question most asked since then has been – why did the Rada keep its mandate when all the other Governments in Exile of the Republics of the USSR and of the Soviet Satellite states returned theirs upon achieving independence?

I will try here to answer that question and express my understanding of the reasons why the role of the Rada remains essential today.

Why are we Europe’s only Government in Exile?

When the Soviet Union disintegrated, all Governments in Exile of the former Soviet republics and Soviet satellites returned their mandates to their homelands, except the Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic in Exile.

The immense wave of hope experienced at that time made the oppressed nations believe that the end of the empire would be followed by a general renaissance of the old states harbouring the values which had been preserved for half a century by their exiled governments. It did. Belarus was one of the exceptions because the governmental structures in place had not been established through free elections.

The human factor has not played a lesser role. Because of its geopolitical interest to Russia, and its proximity to Moscow, the Belarusian territory had been more than any other Soviet republic made the homeland of a new Sovietized, totalitarian type of personality – which we know under the name of homo sovieticus. Intended to be the ideal citizen of a new Soviet order, its main characteristics were a total ignorance of his pre-Soviet past, the acceptance of the “big brother” status of Russia, the replacement of his/her mother tongue, ancestral culture and values by Russian language and Russian cultural and historical values. A sense of another “national identity” was called “bourgeois nationalism” in all non-Russian republics.

Granted that our people were not opposing Moscow’s russification policies. Having experienced two world wars on their territory and years of Soviet terror, deprived of freedom since the partitions, bereft of historical memory, Belarusians had developed incredible survival skills and had adapted to the Soviet ways of life. They were ready to accept anything, as long as there was no war.

Their skills made them one of the wealthier republics of the Soviet Union. So much so that it was literally invaded by two million non-Belarusian Soviet citizens. This is not a xenophobic statement, but rather emphasizes that this influx significantly changed the nature of the electorate in a country of ten million.

A non-democratically elected Parliament, a ”denationalized nation” (See D. Marples), a strong foreign element in the population, were not factors we could ignore, when considering the future of the Rada. I have to say that although there are many Russian émigrés in Belarus who have successfully integrated in the Belarusian society and consider themselves Belarusian, there is still a significant margin of them considering themselves Russian.

However, some key events did energize the momentum of the Belarusian opposition. The discovery of the killing grounds of Kurapaty, and the Chernobyl disaster whose consequences in Belarus had been hidden for three years by the Soviet authorities, had for a short time given rise to a “mutiny” even within the Communist structures of the republic. The small but strong opposition led by Zianon Paźniak would probably have succeeded to put an end to the populations “survival mode” if Belarusians had seen some sign of support or sympathy from the West.

The West, however, saw no interest in this relatively small state, they had considered for a long time as a Soviet creation. “We have to draw the line somewhere” said the Canadian deputy Prime Minister of the time, Sheila Copps, when our community tried to plead for help for Belarus. Among the ordinary Belarusians, hope gave way to Soviet nostalgia.

Aware of the situation, the Rada decided to wait and see. Before returning our mandate, we wanted to be sure that the independence was irreversible and Belarus would not need us any longer. We considered that the BNR Rada – a legitimate Parliament in Exile – was a tremendous asset in our hands, and we were not going to part with it without serious assurances. The decision was unanimous. And soon after, we were proven right. The new President of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenka, elected in 1994, showed less than one year after his election who his masters were. In May 1995, he held his first rigged referendum by which he reintroduced the Soviet-style symbols and Russian as an official language of Belarus. In 1996, Russia rewarded him by preventing his impeachment.

Ever since, our goal has been to protect the statehood of Belarus, – constantly threatened by our increasingly aggressive Eastern neighbor, – while helping the democratic opposition to fight the illegitimate government of Alexander Lukashenka and create a modern European Republic of Belarus.

Our present role

In December 2001, Edward Lucas, in The Economist, quoted an Estonian exiled politician who stressed that by its very existence a government in Exile does a job.

The BNR Rada, or the Belarusian Government in Exile, could have chosen to be simply the symbol of a free Belarus. That symbol was still badly needed n Belarus. We held this role at the end of the term of my predecessor Dr Sažyč, at the beginning of the nineties, when we felt we had done all we could to put Belarus on the map of the world, and that it was the turn of the people in Belarus to fight for freedom and a better future. That was until the election of Mr. Lukashenka and the 1995 referendum.

The Diaspora supporting the Rada has done a lot to bring the attention to Belarus after the Chernobyl disaster. In Canada we created the Canadian Relief Fund for Chernobyl Victims in Belarus and brought thousands of children for a respite to Canada. The Diaspora in other countries helped by sending medicines to Belarus.

We understood how badly Belarus needed friends in the free world. I have been personally convinced that our defeat at the Peace Conference in Versailles of 1919, when the post-World War I international community refused to support the independence of Belarus, was due to a lack of politically placed friends. At the same time, many of our neighbours who proclaimed and preserved their independence between the two World Wars had had friends in strategic capitals…We made it a goal to find friends for Belarus.

We realized what a powerful political instrument culture can be. In order to make Belarus a member of the community of European peoples, and not just a disaster zone and “the last dictatorship in Europe”, we made it a goal to call attention to Belarusian culture wherever and however we can.

But our most important political contribution to the renaissance of Belarusian democracy, to the preservation of Belarusian culture and the protection of Belarusian statehood has been made through direct communication with friendly governments. Those who have lived through similar situations, such as the Czechs, those who have made it their goal to defend democracy in the world; such as the United States of America, those who declare that they are not ready to see human rights violated anywhere in the world; such as Canada. Each of our successes has needed, of course, convincing, presence, and communication on our part. But it has been easier to achieve when we have worked through our established communities in the countries whose help we need, and together with the democratic Opposition in Belarus.

A good example of this activity was the recent Appeal to the European Union, which I signed before the Prague Summit together with Mr. Šuškievič, the first head of State of independent Belarus, Mr. Paźniak, a presidential candidate in 1994 and past leader of the Opposition in the Parliament of the Republic of Belarus, and Mr. Kazulin, the Rector of the State University of Minsk, who was jailed for two years and a half after having competed with Mr. Lukashenka at the rigged 2006 presidential elections. Together with another Presidential candidate of 2006, Mr. Milinkievič, we met with the Prime Minister, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and the President of the Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Commission of the Czech Republic. We thanked the European Union for accepting Belarus into the Eastern Partnership Program in spite of the dictatorial regime of Mr. Lukashenka, while expressing our fear that Europe’s stretched hand may be misused to legitimize the regime instead of serving the people of Belarus. We have asked Europe to include Belarusian civil society into the agreement. And, since the Partnership may prolong Mr. Lukashenka’s stay in power, we have asked Europe to protect Belarusian culture and values, which are presently being destroyed or persecuted in Belarus, and may be totally extinct by the end of his reign. This common appeal has been heard by the Czech hosts of the Summit, who will pass it on to Sweden, the next presiding State of the European Union.

The example I have provided was an event held in the Czech Republic, a long-time friend of the BNR Rada. I have been received there several times at the highest levels. As a representative of a government in Exile, I would probably not have been invited for consultations by France or Germany. The success of our endeavours depends very much on who we are dealing with. As I said, the countries who have been in a similar situation to ours understand well the significance of a Government in Exile. But in most cases, dealing with a Government in Exile is perceived as a conflict of interests, especially where commerce or a given political interest is involved, such as the issue of the Arctic population in the case of Canada and Russia. We understand that quite well. And, at the same time, we have been worried more than once that a rapprochement between the United States and Russia, for example, could theoretically take place at the expense of Russia’s coveted neighbours. I only hope at this specific moment in time that Mr. Obama’s administration is well aware of Russia’s imperialistic instincts.

BNR Rada and Belarus

Last but not least, I would like to address the issue of the relations of the BNR Rada with Belarus. According to many, we have been the light of hope, which has led our freedom fighters in Belarus to our common goal – the independence of our land. Outside Belarus, we have preserved the language, the historical memory, the national identity when they were being erased from the surface of this planet in Belarus. During the period of renewal at the beginning of the nineties, the President of the BNR Rada, Dr Sažyč has been welcome in Belarus as an honourable guest.

We became “the enemies of the people” – together with the Belarusian democratic opposition, – as soon as Mr. Lukashenka became President of the Republic of Belarus in 1994. In a speech at the Russian Duma in 1998, he informed his friendly audience, that a rival of his, a certain Sulvilla or Survilla – an émigré of the first WW and now 97 years old – (a man of course) – was supported by the West. After the Prague Appeal was signed by myself and the main representatives of the Belarusian democratic opposition, asking Europe not to legitimize the regime by inviting Mr Lukashenka to the Prague summit, he lumped us all into the “enemies of the people” category.

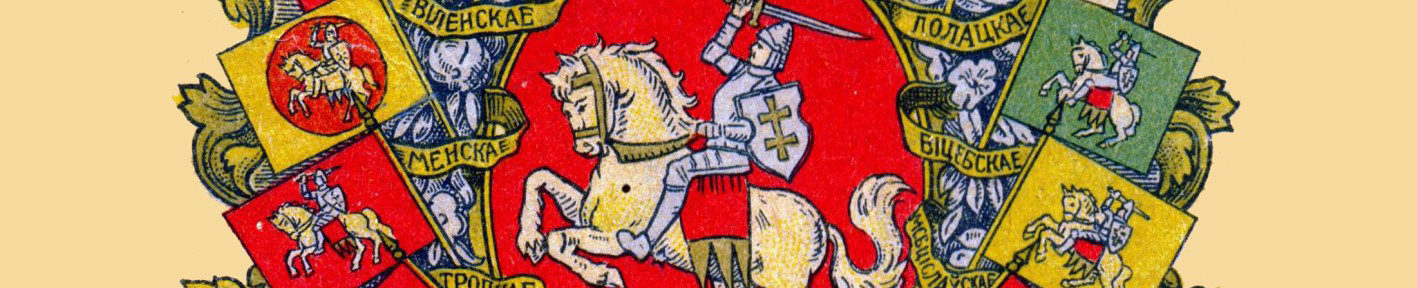

The national white-red-white flag, the historical coat of arms Pahonia, the very mention of the Rada are taboo in Belarus, except when the intent is their denigration by the propaganda machine. No lie is too enormous to fight us. The brain washing is successful among the ordinary Belarusians who have no access to unbiased information. Thus, we are not always the allies to brag about for the opposition.

Our relationship with most parties of the opposition is however good. When we attend together international events, whatever our difference of thinking, we all know our common goal is to preserve the statehood of Belarus and to make it a free, European democracy. As for the future of the Rada, we can’t wait to be able to give back our mandate to a democratically elected Belarusian government. Our role at that time will very much depend on the free will of the people of Belarus. It will be up to them to decide what kind of democracy they will have. If we feel we cannot be of any use in Belarus, we will continue to look for friends for our people, whom they so tragically lacked in the past centuries.

There is no doubt that a government in Exile is an exotic idea for many. Such a government exists out of necessity and operates according to many challenges, dilemmas and varying acknowledgments of its empowerment. My experience in this organism has been at times frustrating, at times satisfying. I have been privy to the variety of perceptions of Belarus and the correlations between global buy-in and the willingness to understand the conditions of existence of such a government. But whether the Rada is universally accepted is less important than our constancy of presence. We function on the idea that we are part of a process toward democracy, and that by our existence we can mediate the political nuances that must be understood in order to change conditions in Belarus.

Ivonka J. Survilla